Functional Core, Imperative Shell

How does someone get something done in a purely functional language? A pure function is not allowed to mutate a variable, or draw something to a screen, or play a sound, or write a file to disk, or even print out a string.

It sounds like a program written with only pure functions can’t do anything useful. If you had that thought, you would in a sense be right, but it’s not the whole story.

There are some notable projects written in Haskell, such as back-end services (NoRedInk comes to mind) and games like Defect Process on Steam. The developers of these must manage to get by one way or another, but how?

The answer is by separating pure functions from those impure functions performing IO. Let’s try to understand what that means a little more clearly.

How do I separate pure functions from IO?

Generally, every non-trivial program can be decomposed into three stages: input, process, and output.

Input

The input stage gathers whatever data we would like to act on.

On a server, we might consider the input stage as a document fetch.

For a game, input may involve checking keyboard or mouse events. This stage is often impure because the method to retrieve input (such as checking the status of IO devices) is impure.

Processing

The processing stage takes the input from the previous stage, and… processes it.

The processing might involve modifying existing state objects in a game, returning a new object to later be saved in a database, or a number of other things.

The key point is that it acts on the input (and possibly some other state/data) and prepares for the output stage.

Output

The output stage for a non-trivial program always consists of an impure function, doing something like drawing to a screen, saving to a file, or updating an object in a database and responding to a user with a HTTP status code.

A digression: the above diagram shows an optional loop. This is meant to represent long-lived processes like games, UI applications and web servers. They typically have an infinite loop where they start cheecking for input again, after performing output.

A program might have these three stages somewhat tangled together, but untangling these into separate parts is often inmportant in functional programming.

The idea is for most of the code to be in the processing stage, which takes input values and returns a new state object (not modifying any existing state). This new object is passed off to the output stage.

Most of the code you write should be in the processing stage which can consist solely of pure functions. The code for the input and output stages should be a thin layer of imperative, side-effecting code that is quite minimal in comparison.

The separation in practise

We can see some example code of what the separation might look like. I have a somewhat simple implementation of Pong Wars here.

The most instructive file to look at is shell.sml, which is the program’s entry point and its imperative shell.

This file does the following:

- It creates a window and initialises OpenGL and GLFW

- It creates an initial game state

- In a loop, until a window-close is requested:

- It calls a function which, given a game state, returns a new immutable game state with some different data. (At the very least, the players will be in different positions. If either player knocked the other side’s blocks, those blocks will also be flipped.)

- It draws the new game state.

In this example, the pure segment of the code is the update function which takes an immutable game state and returns a new immutable game state.

The draw function is inherently side-effecting and belongs to the imperative shell. The update function is by far the more complicated part, which is good because that is also the most testable.

So, mapping to our little diagram above:

- There is no significant input to speak of as the program does not react to keyboard or mouse events or anything except the previous game state.

- The processing part is, of course, the update function which is purely functional.

- The output is an impure function drawing to the screen based on the updated state.

Handling more types of side-effects

We might feel from this simple example that the architecture seems a bit limited. The IO we perform (drawing to the screen) looks fixed and it’s not clear on how we could perform more side effects.

What if we find out while processing in the functional core that we would like to write to a file or perform a network request? Do we need to make the processing impure after all?

Not really. There is no need to make the processing impure if we find out that we need to perform a side effect. We just need to make a few small modifications in the processing function and the imperative shell.

- In the processing function, we store some data in the returned state indicating that we want to perform some IO functions.

- When the imperative shell has finished calling the update/processing function, it checks the new state to see if any side-effects need to be performed. Then it performs them, still in the imperative shell.

This might be a bit abstract, so let’s consider the outlines of what code doing this may look like.

First, we define a sum type (an enum which may contain arbitrary data; some mainstream languages don’t have this feature).

datatype io_cmds = SaveGame | LoadHighScoreLeaderboard | ...

Secondly, we add a list of our io_cmds type to the state we return.

type state = { cmds: io_cmds list, ... }

Thirdly, we add an instance of the io_cmd type to the state in our processing function. The resulting list may look like this:

[SaveGame, LoadHighScoreLeaderboard, ...]

Next, in our imperative shell, we fold over the list in the game state.

Then, with pattern matching, we detect which IO commands we need to execute and actually execute them. (We may want to update the state based on the output of those commands which is fine too.)

Finally, because all of the IO commands are done (or currently running if asynchronous), we modify the io_cmds list in the state to be empty. Then we simply continue the loop, as usual.

This isn’t the only way to handle more types of IO in the architecture, but it is my preferred way because sum types are quite easy and descriptive compared to checking various parts of the state using if-statements.

Maximise your functional core

If we look at the call graph of the Pong Wars program, we will see that the program as a whole will be considered impure.

One impure operation (like drawing) is enough to “contaminate” the call graph from that impure function upwards.

All the functions that call our drawing function (those that depend on it directly or indirectly) are impure too, but it’s not necessarily the case that those functions which the drawing function calls (those it depends on) are also impure.

For example, look at game-draw.sml click here in the Pong Wars repository. The three impure functions there are:

draw, which simply calls the two belowdrawBlocksdrawBalls

The drawBlocks and the drawBalls functions don’t have any significant logic of their own, although they are quite long because OpenGL is just verbose.

These two functions use the results of two pure functions they call (drawBlocksLine which is a misnomer in that it builds vertex data rather than drawing, and the more appropriately named ballToVertexData).

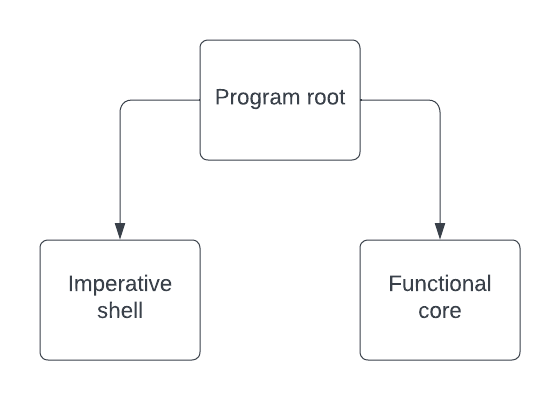

So, it may not be useful to think of the Functional Core, Imperative Shell architecture as being like the diagram below where we have two parts (the functional core and an imperative shell).

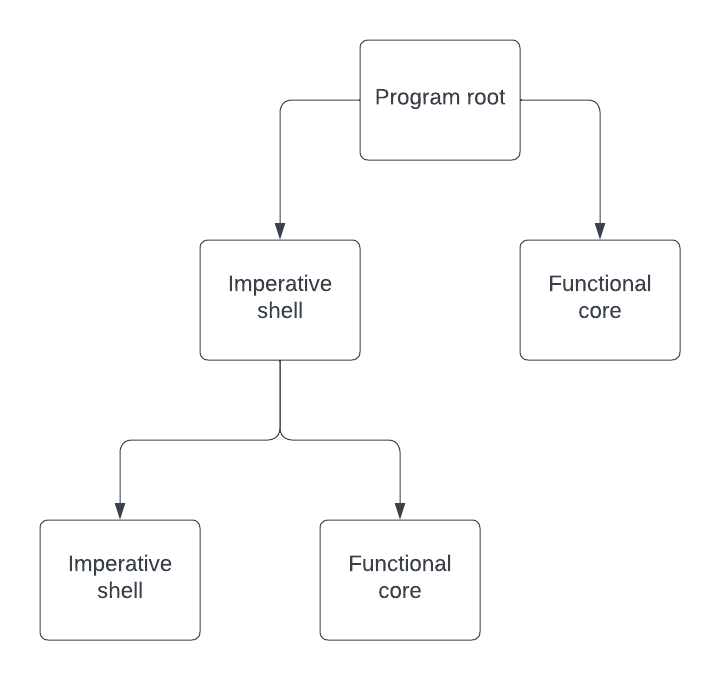

Instead, we can try to maximise our benefits from this architecture by designing the imperative shell as having a functional core within itself as the below diagram shows.

This lets us reap more of the benefits that functional programming offers us. It is easier to reason about (which I think is the biggest advantage), it is more testable, it is more scriptable and so on.

Further information

The best explanation that I’ve seen about this architecture (which is a term I prefer in this case to “design pattern” because it applies to the whole program) is Gary Bernhardt’s talk on boundaries, which I recommend.

He talks more about the benefits of the architecture and how it eliminates the need for mocks in testing.